"[Sigmar] Polke's pictorial inventiveness is so generous, so viewer-friendly, it makes you feel that, on a good day, you too could do it. His paintings get at something elemental about how to live today, and seem to whisper 'You are not locked into your story. You could be otherwise.' The strength of that conviction, the sheer vitality of it—I can't think of anything more we could ask from art."

Some sentences stay with you, lingering like an afterimage. They are sticky; they grab you by the throat. David Salle's How to See is full of those sentences. Words that stir a visceral reaction. In this collection of essays, he brings the world of art to life and suggests something radical: to understand art, you have to look at it. And think about how it makes you feel. It is as simple as that. Sort of.

"We need to pay attention to what a work of art actually does—as distinct from whatever may be its supposed intention."

I recently visited a highly anticipated museum exhibit. It had rave reviews. But as I wandered the rooms, I felt lost, not in a good way. The works were loud, not in volume but in message. Each piece clamored to be heard, so much so that together, they drowned each other out. It was like being shouted at from all sides. Afterward, I felt numb, drained, and sort of bored. There was a ringing in my ears.

I called my mom (as one does when having an existential crisis) and told her I must have been missing something. Why did I hate this show? I thought the problem was me. After all, this was a major institution curated by someone who obviously knew more than I did. But then I read David Salle. And suddenly, I had the words to describe my experience. Salle gave me a new framework—or maybe just permission—to trust my experience. To believe, as Salle does, that intentionality can be overrated, that a piece of art can stand on its own.

Salle invites us to look at what a work of art looks like before asking what it means. His philosophy aligns with how many people intuitively experience art: through visual impact and emotional resonance, rather than intellectual decoding.

"How does one learn to really look at things? I think it's a good practice when looking at anything to try to be aware of what you actually find yourself thinking about—which is often different from what you know you're supposed to be thinking about."

We often feel that to understand art, we need to be fluent in its history, the artist's biography, the cultural and political context, and the message it conveys. But that keeps people at a distance from the art itself.

"The trouble of trying to judge art today is that too many reputations are based on fluency in the reading of cultural signs, something that gives people the feeling of being in on the game."

So here is a kind of manifesto for how to look at art—a collection of ideas from Salle, peppered with some of my favorite examples of his writing:

How To Look At Art:

Salle is not suggesting that you turn off your brain, mindlessly glancing at art the way we might scroll our social media feed. Instead, he puts forth a way of experiencing art rooted in the image itself. He suggests you look to the style, form, and most importantly, the work's “bottom nature1” or “inside energy2.”

1. How Does It Make You Feel?

First, pay attention to your own reaction. Salle often uses analogy to get to the essence of a work. His writing makes you feel the art, even if you've never seen the piece. What does the work remind you of? What experiences, memories, or feelings arise?

On Amy Sillman: "The paintings felt like memories of houses you never actually lived in."

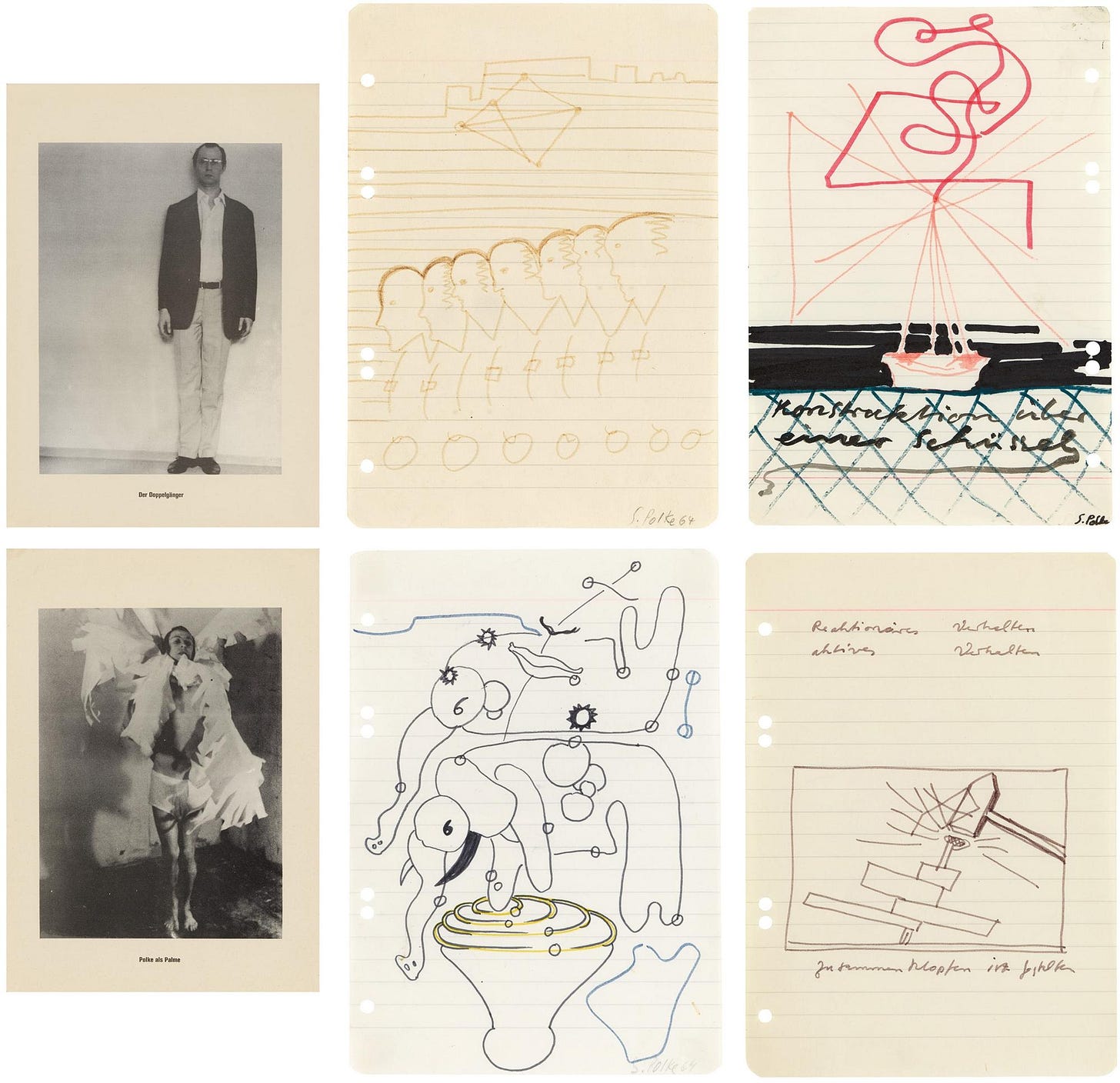

"Part of what [Sigmar] Polke does… is to give the viewer access to the deep pleasure that comes with seeing the familiar as something irrationally strange."

On Jack Goldstein's work, "they're like facts that can't be argued with"

"The experience of a Wool painting starts with reading but is more like being read to; as we look, a void other than one's own intrudes. Wool's painting directly addresses the viewer: to look is to be harangued; these paintings come with their own megaphone."

That last quote captures Salle's gift. He doesn't describe what a painting means; he explains what it does. He gets at the emotional tenor, the dynamic charge, the effect. And that effect is where the art lives.

2. What Does It Look Like?

Salle has an incredible vocabulary for describing visual components—color, line, structure, texture, and gesture. He has a way of animating a static image with language.

Color:

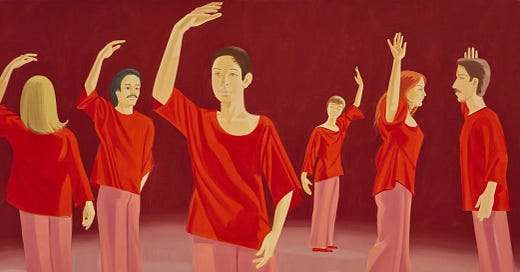

On Alex Katz: “In painting, the specificity of color is everything. That orange next to this brown, with a tiny bit of that exact shade of celadon as a bridge.”

“Aldrich’s palette here is sophisticated, just shy of decoratorish; he takes eight or nine hues and nudges them into perfectly tuned intervals of cream, white, Pompeii red, burnt umber, and a grayed cobalt green–color that feel at once Mediterranean and Nordic.”

Form:

On Polke: "chunky, visceral drawings" "lyrical," "angelic," or "absurdist humor within the form" On Sillman: "lilting and fluttering quality of flags that move with the wind" On Baldessari: "decorative, charming, clumsy, and a little weird"

It’s not one word. It’s the unexpected combination that brings it to life.

Style and content:

Salle often touted the importance of style - he believed that this was 50% of the equation for good art, the other was imagination. He believes that lasting art is permeated with an intense observation of the world as it is.

“[André] Derain sought to combine the classical with the anecdotal, to squeeze one into the other, almost with his bare hands. He painted everyday life, the view out the window, the people around him, but with one eye on his forebarers; with a sense of compression and narrativity one gets from bringing an updated version of the past into the present.”

“When people say that surrealism borrows from the logic of dreams, what they mean is that objects, people, things undergo transformations without going through any visible transition. In surrealism, as in dreams and cartoons, things turn into other things without preamble.”

This last quote is not about the message Surrealism touts, or its historical context; it is purely about its style. What it does, what the viewer experiences.

Putting it all together:

Salle’s most powerful descriptions put it all together. Color, style, texture, and feeling, reconciling form and content:

On Derain, “His paintings, from the teens onward have a wrought quality; the white tableclothes are like plaster-soaked rags twisted between his hands. He wrestled with form, and lets that wrestling show. His forms seem hacked from larger solids as if with a machete; shapes are contorted and their edges lifted ragged. His subject matter–all the classical genres: still life, portraits, landscape, nudes–can produce a surprising narrative tone. He somehow makes a painting of a tree feel whistful, nostalgic.”

Again on Derain: “his pictures give a palpable sense of the way forms in painting, much like a secret handshake, can be transmitted across time.’

3. What Was the Process?

Salle also writes with rare intimacy about the process. As a painter himself, he understands the physicality of making. Salle calls out the failure of art history to account for why someone would go to all this trouble. What it feels like to make something. The vulnerability, the struggle, the curiosity.

“Derain’s story interests me, in part, because he exposes the ‘narrow and croacked determinism,’ to borrow a phrase from Joan Didion, of contemporary art history, the more or less complete failture of that history to take into account what it actually feels like to make soemthing, the why of it–why someone would want to go to the trouble– s well the specific feeling of looking at it. Like determinism in any walk of life, aesthetic as well as political, the wish to have it a certain way is at odds with what people are really like.”

4. What Is the Message?

This is the least important question, according to Salle. In fact, a heavy-handed message often sinks the work.

“Today talent is easily confused with knowingness or a desire for attention, and what passes for imagination is often nothing more than a reshuffling of cultural signs.”

“Often what passes for an idea is, on closer inspection, really propaganda– someone wants something, wants to promote something.”

“Art that shores up an already ratified position, or illustrates today’s headlines, is likely to have a brief shelf life.”

Salle urges us to be suspicious of overly clever work that rearranges familiar cultural references to say, "Look how much I know."

Art That Lasts

Great art has stakes. It integrates form and content. It feels emotionally and visually full. It gives more than it demands. It stays with us.

“The qualities we admire in people–resourcefulness, intelligence, decisiveness, wit, the ability to bring others into the emotional, substantive self–are the same ones we feel in art that holds our attention.”

“To make something that really holds our attention, especially over repeated viewings, requires levels of integration–intellectual, visual, cultural–expressed with a unique physicality. Art that eschews this integration is unlikely to be durably compelling for the simple reason that less is at stake. Chances are, the tension of vulnerability and the emotional power will be diminished. Over time, the result will have the flavor of commentary.”

David Salle’s How to See is less a manual and more a provocation—a reminder that art isn't a puzzle to solve, but a conversation to enter. It encourages us to resist the pressure to decode and instead linger in our own perception. This collection of essays does what the best art criticism should do: it deepens our attention, sharpens our instincts, and gives us language for experiences we already intuitively understand. Salle doesn’t offer a singular doctrine, but he does offer clarity. And in doing so, he reminds us that the act of looking deeply, personally, and with feeling is enough.

What’s new at LES:

Our newest launch celebrates the artist’s hand—its imprint, gesture, and calm authority. Whether shaping clay or sculpting in wax destined for cast metal, each maker leaves behind a signature entirely their own. These works were selected because of how they carry that presence—for their personality, and the way the artist’s spirit hums just beneath the surface. You can feel it in every curve, every edge, every intentional imperfection. There’s a richness in how the hand reveals itself—honest, intimate, and deeply felt. To bring these pieces into your home is to welcome that same sense of soul and artistry into your everyday.

Featuring: Sasha Court, Sierra Kanistanaux, Talia Shells, Stacy Solodkin, Tina, Kristen Yezza, and Lillain Smith

That’s all for today! Thanks for reading!

If you liked this, please share it with a friend, leave a comment, and subscribe! For more creativity, you can follow us on IG and explore years of art and design articles on the LES Journal

Keep Reading…

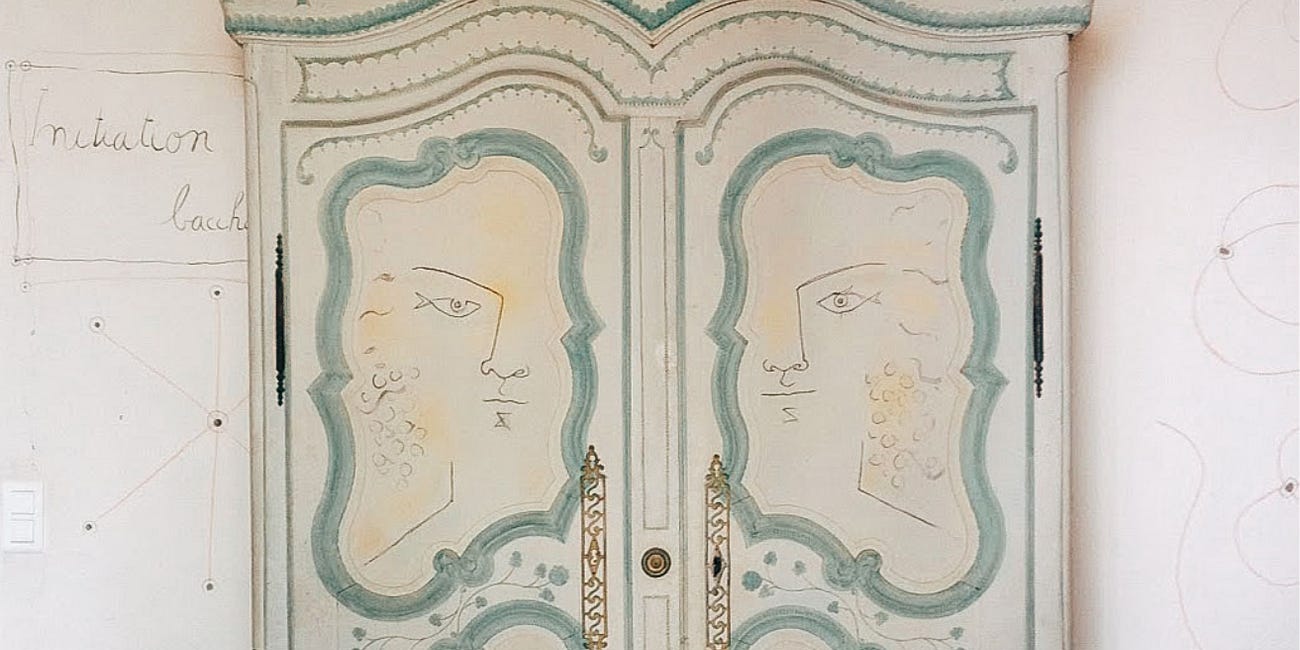

Design Lessons From The French Riviera

What would it be like to live inside a myth—surrounded by a dream? I imagine that's what it would feel like to step into Villa Santo Sospir on the Côte d'Azur. To be submerged in the murals of Jean Cocteau. To soak in his vibrant palette and gestural, mythic linework. It's as though Cocteau dipped his brush …

Fashion Detox: Why I Gave Up Buying New

Last September, I set a challenge for myself: no new clothes, shoes, or bags until the end of the year. By "new," I mean anything freshly made, never owned, straight from the factory floor. Vintage and secondhand were fair game.

How To Sell A Luxury Product

Did I get you with that title? Are you sufficiently invested? Do you want to know the answer? Me too. I have spent an inordinate amount of time thinking about what luxury means to people. The following is not just for someone trying to sell a luxury product but for anyone who cares about thoughtful consumption and the luxury experience today. At LES, we…

A phrase Salle borrows from Gertrude Stein

A phrase Salle borrows from Alex Katz

Thank you for sharing!